Sample chapter

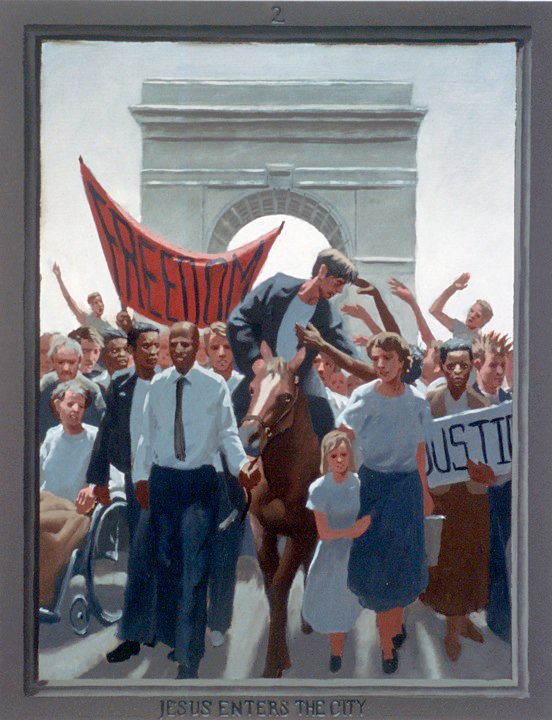

2. Jesus Enters the City

“And when he entered Jerusalem, all the city was stirred, saying, ‘Who is this?’ And the crowds said, ‘This is the prophet Jesus.’” —Matthew 21:10-11

A diverse 21st-century crowd marches under an arch with a charismatic young man in Jesus Enters the City. Signs for “freedom” and “justice” make it a rally for almost any cause, from marriage equality and LGBT rights to the Occupy movement or the Tea Party. The masses adore Jesus as if he was a rock star or political leader. They stretch their hands up to him, grasping for the savior that they expect him to be. Jesus has brought together a varied group: male and female, multi-racial, young and old, queer and straight, able-bodied and wheelchair-bound. A mother and daughter lead the way, along with a black man who holds the reins of the horse that Jesus rides. By passing through the arch, Jesus leaves his old life behind to meet the new challenges ahead.

Arms raised, the people rejoice, but the sky is grey and they are not united. Their signs droop or get blocked, making them hard to read. Each person looks in a different direction, never making eye contact. As the Passion story begins, Jesus seems disconnected from the passions he stirs in others. The seeds of conflict are already planted. In the middle of this “triumph,” Jesus bends down to be embraced by someone unnoticed and out of view. He is focused on something that others ignore. The crowd marches forward, about to step right out of the picture frame. The viewer can’t see what Jesus sees, and the oncoming group will force viewers to make a decision: join in, back off, or get trampled underfoot. Light from the arch forms a lopsided halo behind his head.

There are no palms in Blanchard’s generic cityscape, but this is an updated vision of Palm Sunday, which commemorates Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. All four gospels describe how Jesus entered Roman-occupied Jerusalem at the height of his popularity. Enthusiastic fans greeted him by laying palm branches on the ground before him and shouting “Hosanna,” which translates as “Save us now!” Huge crowds were gathering in Jerusalem for the Jewish festival of Passover. They saw Jesus as a political deliverer who came to fulfill the ancient prophecies of a messiah: an earthly king anointed by God. His arrival on a donkey reminded them of the victory processions of ancestral kings descended from David. By riding a lowly donkey instead of a war horse, he hinted that he came in peace. They mistakenly thought that Jesus was declaring himself king of Israel, ready to lead a rebellion against the Roman army. Palm Sunday hints at the trade-offs that people make in pursuit of power. As the crowds marched into Jerusalem with Jesus, they were already on the path that would lead to his destruction. Their movement was gaining momentum on a trajectory that could not be altered or stopped. “If these were silent, the very stones would cry out,” (Luke 19:40) Jesus told the traditionalists who wanted him to quiet the crowd.

Jesus’ triumphant entry foreshadows the emptiness and impermanence of earthly glory. Luke’s gospel says that Jesus wept over the city when his procession got close to Jerusalem, the center of Jewish religious and national life. More than once in the Bible he lamented over Jerusalem’s inability to recognize God’s prophets. He longed to gather its people together “as a hen gathers her brood under her wings,” but they refused. Jesus signaled a power not of this world, while they sought worldly power. He was surrounded by adoring crowds on the way to Jerusalem, but they were not the true community that would be forged by the hardships ahead. Every hero’s journey begins with entry into a new place. On Palm Sunday Jesus leaves behind his old life as an itinerant teacher and healer, crossing through a gateway to face death itself for the good of all.

Crowd scenes are one of Blanchard’s strengths as an artist. He makes fine use of that talent in Jesus Enters the City, which is one of the most popular images in his whole Passion series. He can capture a crowd’s unruly movements almost like a stop-action camera. Indeed while working on this series, the artist studied Charles Moore’s photos of the American civil rights movement. Blanchard paints each face in the crowd as a unique individual. For example the young man in a spiky mohawk carrying the “justice” sign on the right looks like he just stepped out of a LGBT Pride march. Most artists from history have shown Jesus marching through the gate in profile or three-quarter view, but Blanchard takes the unusual step of making Jesus head straight at the viewer.

Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem is one of the oldest Christian images. It can be found among the earliest Christian artworks in the catacombs of Rome, where the fourth-century sarcophagus of Junius Bassus shows Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. The image follows a tradition in Roman Imperial art of depicting the formal arrival (adventus) of the emperor into a city during or after a military campaign. Christ entering Jerusalem has been portrayed by many great artists from the Middle Ages to the Baroque era. One of the oldest and best-known versions is a fresco painted by Giotto in 1305 at the Arena Chapel in Padua. German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer engraved it in his Small Passion series, which Blanchard acknowledges as a source for his gay vision of the Passion. But the scene is omitted from the traditional Stations of the Cross, which instead starts days later when Jesus is condemned to death. Modern artists have mostly ignored Palm Sunday in favor of other episodes from the life of Christ. An exception is Swedish photographer Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin. She re-envisioned Jesus’ life in a contemporary LGBT setting with notorious 1998 series named Ecce Homo. Her version of the arrival in Jerusalem shows Jesus riding a bicycle in Stockholm’s festive LGBT Pride Parade.

Triumphal arches were invented by the ancient Romans and remain one their most influential architectural forms. The arch in this painting is a simplified version of the Washington Square Arch in New York City, where Blanchard has lived since 1991. It is a landmark in Greenwich Village, an artsy neighborhood with a nonconformist tradition. That arch was in turn based on the first-century Arch of Titus in Rome, which also inspired the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. The Arch of Titus was built to commemorate the siege of Jerusalem, yet ironically in this painting it serves as the gateway to Jerusalem for the doomed Jesus. The Arc de Triomphe played a role in military victory rallies for rulers from Napoleon to Hitler. In 1999 a new version aggrandized a contemporary kind of empire: a Las Vegas casino. All of these arches stand for material power, and thereby hint at its transience as times change.

Arriving in a city is often an LGBT rite of passage. Many queer people leave their homes to find freedom in an urban mecca where they congregate and form their own communities. Marching in an LGBT Pride parade for the first time is an experience not unlike Jesus’ triumphal entry. Pride marches celebrate LGBT culture and serve as demonstrations for equal rights. Like Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem, Pride parades are raucous, wildly joyful celebrations—and they can mask potential hazards. The LGBT community is not immune from the dangers that have plagued underprivileged groups since before Jesus’ time: In the quest to gain political power, communities can lose touch with the true power that they already have through their unique culture, spirituality, shared history, and connection with each other. Hostile outside forces can take advantage of internal divisions to crush any leaders who rise up to defy the system.

Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Holy Week, a period of reflection on Christ’s Passion leading up to Easter. With this second painting in the series, Blanchard dives into the ambitious project of telling the Passion story in a contemporary urban setting from a gay perspective. The action will not stop until the final painting. Let the adventure begin!

_____________________________________________________________________________

“Look, the world has gone after him.” —John 12:19

Everyone cheered when Jesus called for justice and freedom. Crowds followed him into the city, shouting and waving. Their chants were not so different from ours: “Yes we can! Out of the closet and into the streets! We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!” Jesus was a superstar making a grand entrance. But he did it in his own modest, gentle style. He surprised people by riding on a donkey. Some of his supporters, those who had mainstream success, urged him to quiet the others—assimilate, don’t alienate. Tone it down. Act respectable, don’t demand respect. Stop flaunting it. His answer: I’m here to liberate people! If the crowds were silent, the stones would cry out! It was that kind of day, a Palm Sunday sort of day, when everyone shouted for equality and freedom. But was anybody still listening?

Hey, Jesus, here I am!

_____________________________________________________________________________

A diverse 21st-century crowd marches under an arch with a charismatic young man in Jesus Enters the City. Signs for “freedom” and “justice” make it a rally for almost any cause, from marriage equality and LGBT rights to the Occupy movement or the Tea Party. The masses adore Jesus as if he was a rock star or political leader. They stretch their hands up to him, grasping for the savior that they expect him to be. Jesus has brought together a varied group: male and female, multi-racial, young and old, queer and straight, able-bodied and wheelchair-bound. A mother and daughter lead the way, along with a black man who holds the reins of the horse that Jesus rides. By passing through the arch, Jesus leaves his old life behind to meet the new challenges ahead.

Arms raised, the people rejoice, but the sky is grey and they are not united. Their signs droop or get blocked, making them hard to read. Each person looks in a different direction, never making eye contact. As the Passion story begins, Jesus seems disconnected from the passions he stirs in others. The seeds of conflict are already planted. In the middle of this “triumph,” Jesus bends down to be embraced by someone unnoticed and out of view. He is focused on something that others ignore. The crowd marches forward, about to step right out of the picture frame. The viewer can’t see what Jesus sees, and the oncoming group will force viewers to make a decision: join in, back off, or get trampled underfoot. Light from the arch forms a lopsided halo behind his head.

There are no palms in Blanchard’s generic cityscape, but this is an updated vision of Palm Sunday, which commemorates Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. All four gospels describe how Jesus entered Roman-occupied Jerusalem at the height of his popularity. Enthusiastic fans greeted him by laying palm branches on the ground before him and shouting “Hosanna,” which translates as “Save us now!” Huge crowds were gathering in Jerusalem for the Jewish festival of Passover. They saw Jesus as a political deliverer who came to fulfill the ancient prophecies of a messiah: an earthly king anointed by God. His arrival on a donkey reminded them of the victory processions of ancestral kings descended from David. By riding a lowly donkey instead of a war horse, he hinted that he came in peace. They mistakenly thought that Jesus was declaring himself king of Israel, ready to lead a rebellion against the Roman army. Palm Sunday hints at the trade-offs that people make in pursuit of power. As the crowds marched into Jerusalem with Jesus, they were already on the path that would lead to his destruction. Their movement was gaining momentum on a trajectory that could not be altered or stopped. “If these were silent, the very stones would cry out,” (Luke 19:40) Jesus told the traditionalists who wanted him to quiet the crowd.

Jesus’ triumphant entry foreshadows the emptiness and impermanence of earthly glory. Luke’s gospel says that Jesus wept over the city when his procession got close to Jerusalem, the center of Jewish religious and national life. More than once in the Bible he lamented over Jerusalem’s inability to recognize God’s prophets. He longed to gather its people together “as a hen gathers her brood under her wings,” but they refused. Jesus signaled a power not of this world, while they sought worldly power. He was surrounded by adoring crowds on the way to Jerusalem, but they were not the true community that would be forged by the hardships ahead. Every hero’s journey begins with entry into a new place. On Palm Sunday Jesus leaves behind his old life as an itinerant teacher and healer, crossing through a gateway to face death itself for the good of all.

Crowd scenes are one of Blanchard’s strengths as an artist. He makes fine use of that talent in Jesus Enters the City, which is one of the most popular images in his whole Passion series. He can capture a crowd’s unruly movements almost like a stop-action camera. Indeed while working on this series, the artist studied Charles Moore’s photos of the American civil rights movement. Blanchard paints each face in the crowd as a unique individual. For example the young man in a spiky mohawk carrying the “justice” sign on the right looks like he just stepped out of a LGBT Pride march. Most artists from history have shown Jesus marching through the gate in profile or three-quarter view, but Blanchard takes the unusual step of making Jesus head straight at the viewer.

Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem is one of the oldest Christian images. It can be found among the earliest Christian artworks in the catacombs of Rome, where the fourth-century sarcophagus of Junius Bassus shows Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. The image follows a tradition in Roman Imperial art of depicting the formal arrival (adventus) of the emperor into a city during or after a military campaign. Christ entering Jerusalem has been portrayed by many great artists from the Middle Ages to the Baroque era. One of the oldest and best-known versions is a fresco painted by Giotto in 1305 at the Arena Chapel in Padua. German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer engraved it in his Small Passion series, which Blanchard acknowledges as a source for his gay vision of the Passion. But the scene is omitted from the traditional Stations of the Cross, which instead starts days later when Jesus is condemned to death. Modern artists have mostly ignored Palm Sunday in favor of other episodes from the life of Christ. An exception is Swedish photographer Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin. She re-envisioned Jesus’ life in a contemporary LGBT setting with notorious 1998 series named Ecce Homo. Her version of the arrival in Jerusalem shows Jesus riding a bicycle in Stockholm’s festive LGBT Pride Parade.

Triumphal arches were invented by the ancient Romans and remain one their most influential architectural forms. The arch in this painting is a simplified version of the Washington Square Arch in New York City, where Blanchard has lived since 1991. It is a landmark in Greenwich Village, an artsy neighborhood with a nonconformist tradition. That arch was in turn based on the first-century Arch of Titus in Rome, which also inspired the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. The Arch of Titus was built to commemorate the siege of Jerusalem, yet ironically in this painting it serves as the gateway to Jerusalem for the doomed Jesus. The Arc de Triomphe played a role in military victory rallies for rulers from Napoleon to Hitler. In 1999 a new version aggrandized a contemporary kind of empire: a Las Vegas casino. All of these arches stand for material power, and thereby hint at its transience as times change.

Arriving in a city is often an LGBT rite of passage. Many queer people leave their homes to find freedom in an urban mecca where they congregate and form their own communities. Marching in an LGBT Pride parade for the first time is an experience not unlike Jesus’ triumphal entry. Pride marches celebrate LGBT culture and serve as demonstrations for equal rights. Like Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem, Pride parades are raucous, wildly joyful celebrations—and they can mask potential hazards. The LGBT community is not immune from the dangers that have plagued underprivileged groups since before Jesus’ time: In the quest to gain political power, communities can lose touch with the true power that they already have through their unique culture, spirituality, shared history, and connection with each other. Hostile outside forces can take advantage of internal divisions to crush any leaders who rise up to defy the system.

Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Holy Week, a period of reflection on Christ’s Passion leading up to Easter. With this second painting in the series, Blanchard dives into the ambitious project of telling the Passion story in a contemporary urban setting from a gay perspective. The action will not stop until the final painting. Let the adventure begin!

_____________________________________________________________________________

“Look, the world has gone after him.” —John 12:19

Everyone cheered when Jesus called for justice and freedom. Crowds followed him into the city, shouting and waving. Their chants were not so different from ours: “Yes we can! Out of the closet and into the streets! We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!” Jesus was a superstar making a grand entrance. But he did it in his own modest, gentle style. He surprised people by riding on a donkey. Some of his supporters, those who had mainstream success, urged him to quiet the others—assimilate, don’t alienate. Tone it down. Act respectable, don’t demand respect. Stop flaunting it. His answer: I’m here to liberate people! If the crowds were silent, the stones would cry out! It was that kind of day, a Palm Sunday sort of day, when everyone shouted for equality and freedom. But was anybody still listening?

Hey, Jesus, here I am!

_____________________________________________________________________________